|

The brochure from Prudential below is a perfect piece about estate planning and taxes. It breaks down information into “Highlights” and “Examples” to ease understanding.

0 Comments

Which investments do you put where to help enhance after-tax returns?

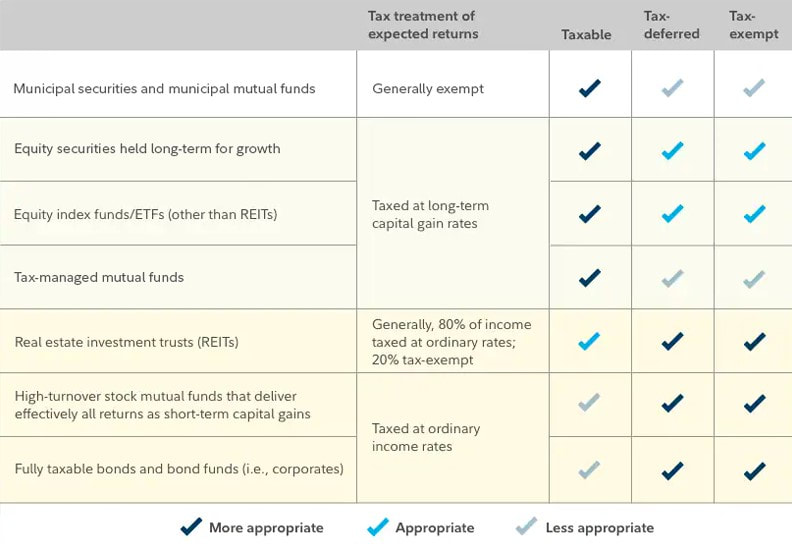

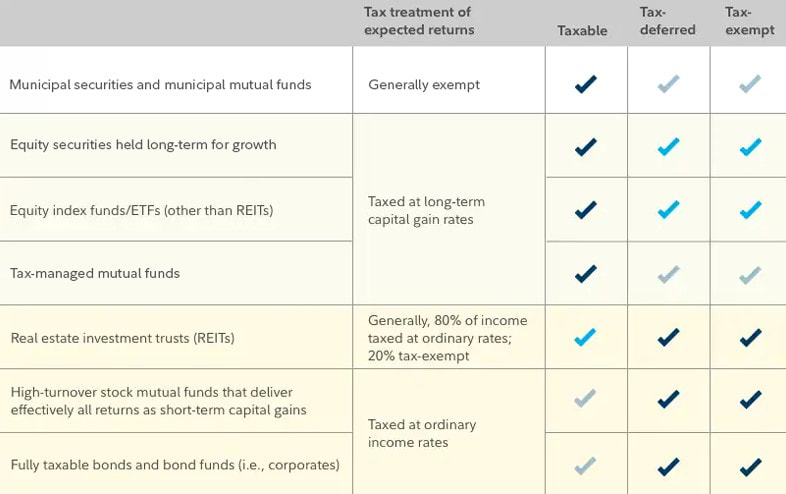

Each person will have to find the right approach for their particular situation. But generally, depending on your overall asset allocation, you may want to consider putting the most tax-advantaged investments in taxable accounts and the least in tax-deferred accounts like a traditional IRA, 401(k), or a deferred annuity, or a tax-exempt account such as a Roth IRA (see chart below). In last blogpost, we discussed how to rank investment on tax-advantaged scale. So, which investments do you put where to help enhance after-tax returns?

Each person will have to find the right approach for their particular situation. But generally, depending on your overall asset allocation, you may want to consider putting the most tax-advantaged investments in taxable accounts and the least in tax-deferred accounts like a traditional IRA, 401(k), or a deferred annuity, or a tax-exempt account such as a Roth IRA. We discussed if you can benefit from active asset location strategy here. Now we will continue the discussion.

If you are in a position to benefit from an asset location strategy, you have to choose which assets to assign to your tax-advantaged accounts and which to leave in your taxable accounts. In general, the following are higher on the tax-advantaged scale:

So, which investments do you put where to help enhance after-tax returns? See next blogpost for the answer. In last blogpost, we discussed what is active asset location strategy. Now we will discuss if you can benefit from it.

There are 4 main criteria that tend to indicate whether an asset location strategy may be a smart move for you. The more of these criteria that apply to your situation, the greater the potential advantage in seeking enhanced after-tax returns.

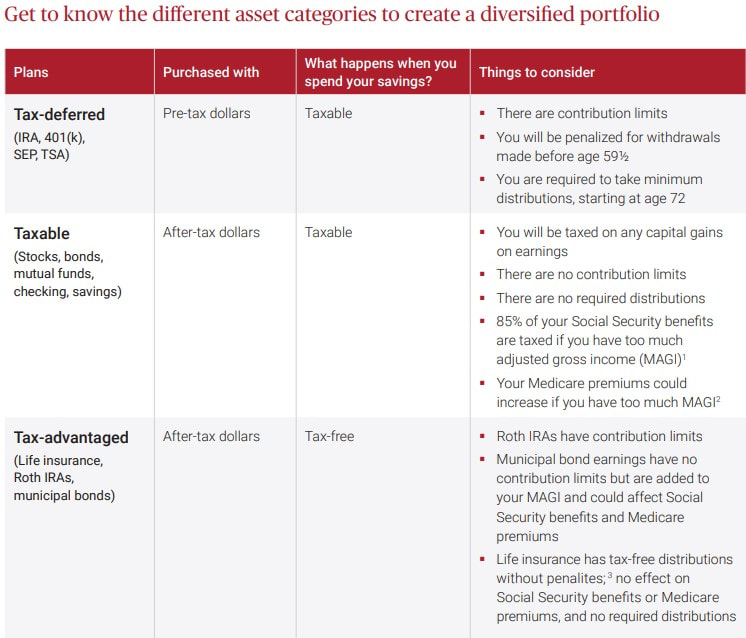

If you are in a position to benefit from an asset location strategy, you have to choose which assets to assign to your tax-advantaged accounts and which to leave in your taxable accounts, see next blogpost here. There are 3 main investment account categories:

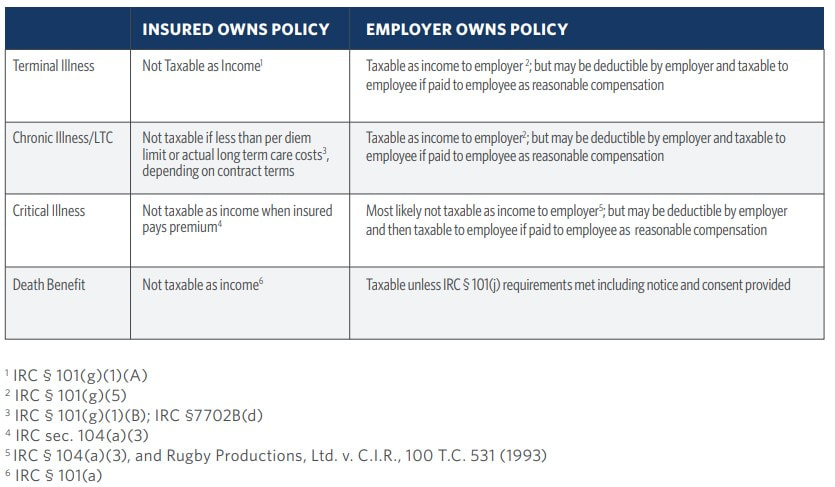

Asset location in action Let's look at a hypothetical example. Say Adrian, age 40, is thinking about diversifying his portfolio by investing $250,000 in a taxable bond fund. For this example, we will assume Adrian pays a 35.8% marginal income tax rate on net investment income and the bond fund is assumed to earn a 6% rate of return each year—before taxes. In what account should he hold the investment? The answer matters, and can mean the difference between paying taxes annually and deferring them until withdrawal. Suppose Adrian has 2 accounts with sufficient assets to choose between, to hold the investment. One is his taxable brokerage account where interest earned on the investment will be taxed annually; the other is a traditional IRA he has been making after-tax contributions to for many years. Since Adrian began contributing to the IRA midway through his career, he never made any tax-deductible contributions. If Adrian chooses to hold the investment in the tax-deferred IRA, the return on his investment, after-taxes, could be nearly $72,000 greater than it would be in the taxable account when he begins withdrawals 20 years later at age 60, assuming his tax rate remains the same. Tax deferral has the potential to make a big difference for investors—especially when matched with investments that may be subject to high tax rates, as interest on taxable bonds can be. In next blogpost, we will discuss if you can benefit from active asset location strategy. The table below compares some of the differences in taxation based on ownership of the life insurance policy:

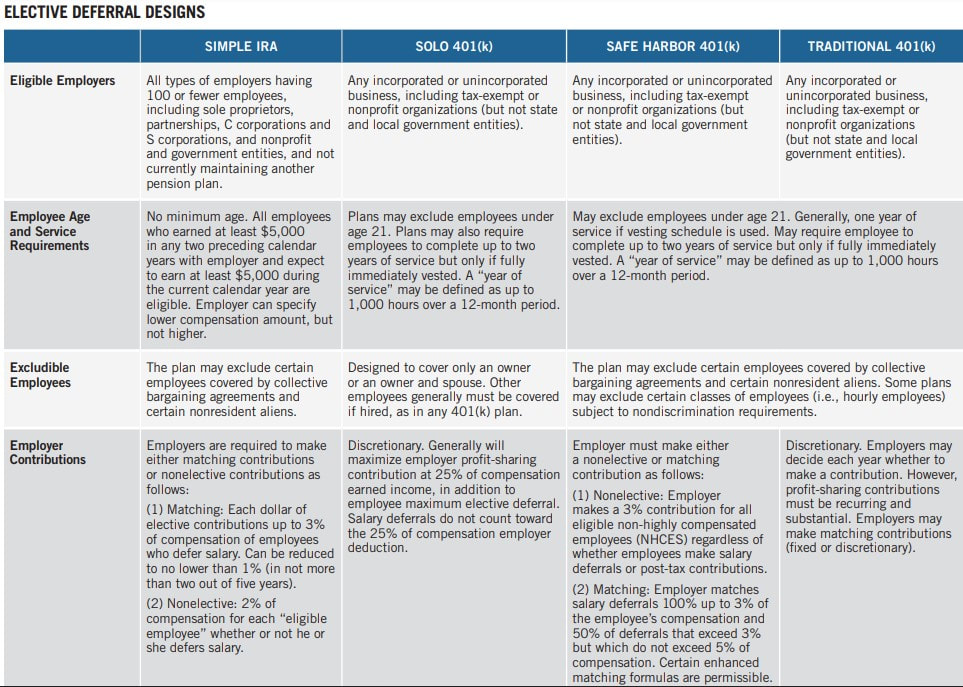

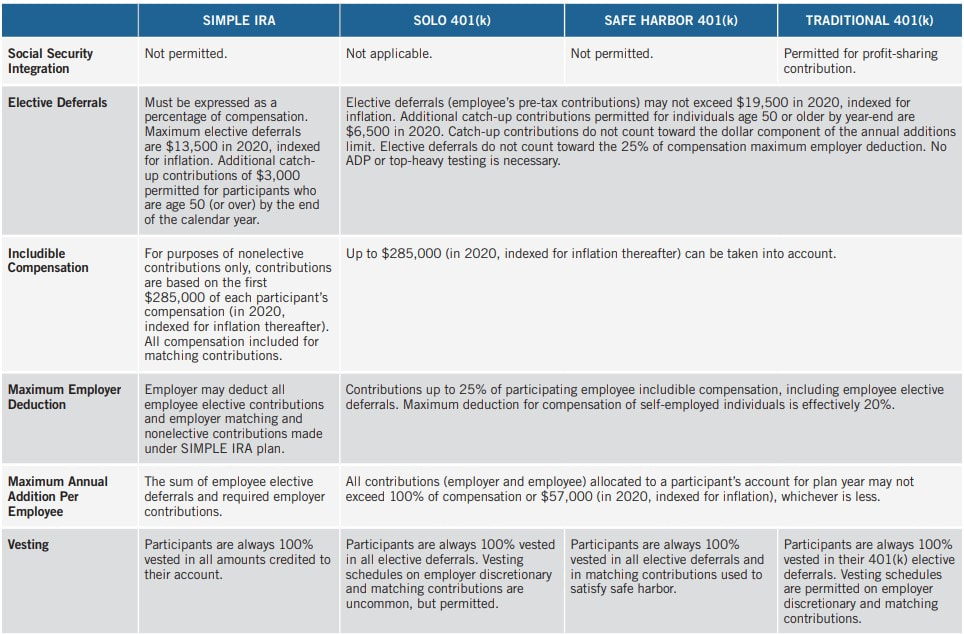

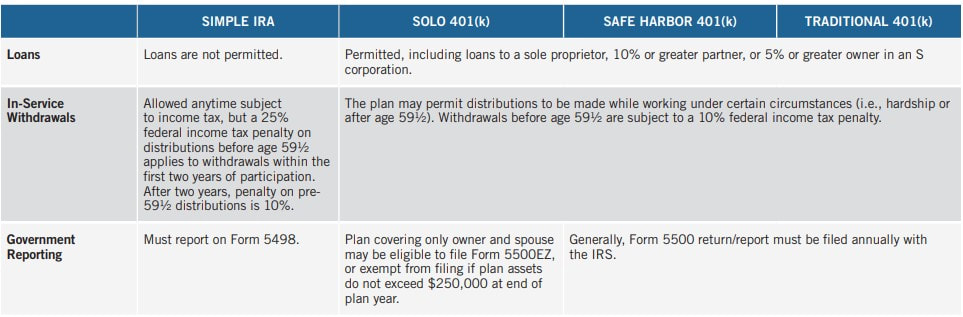

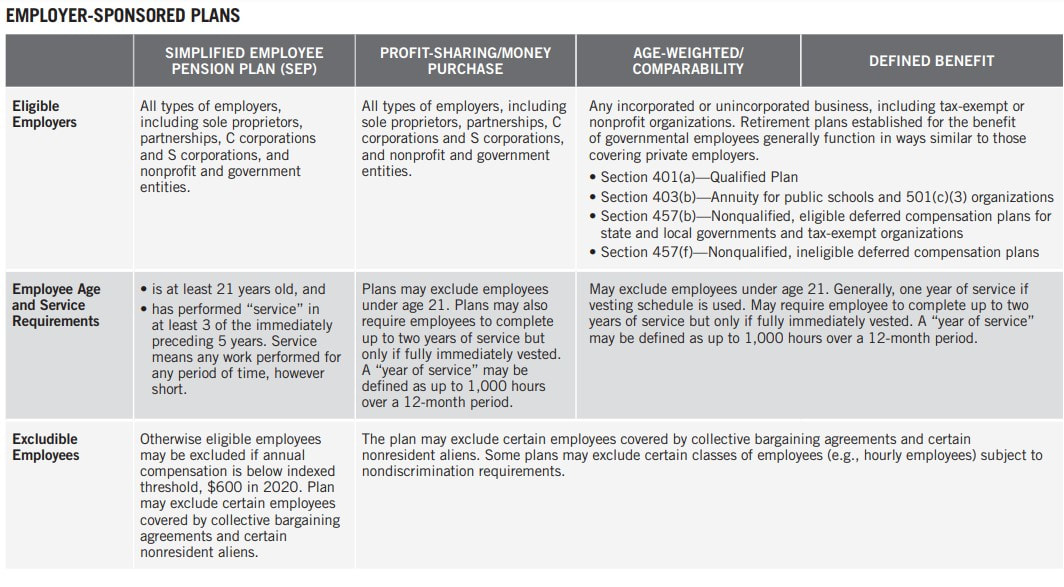

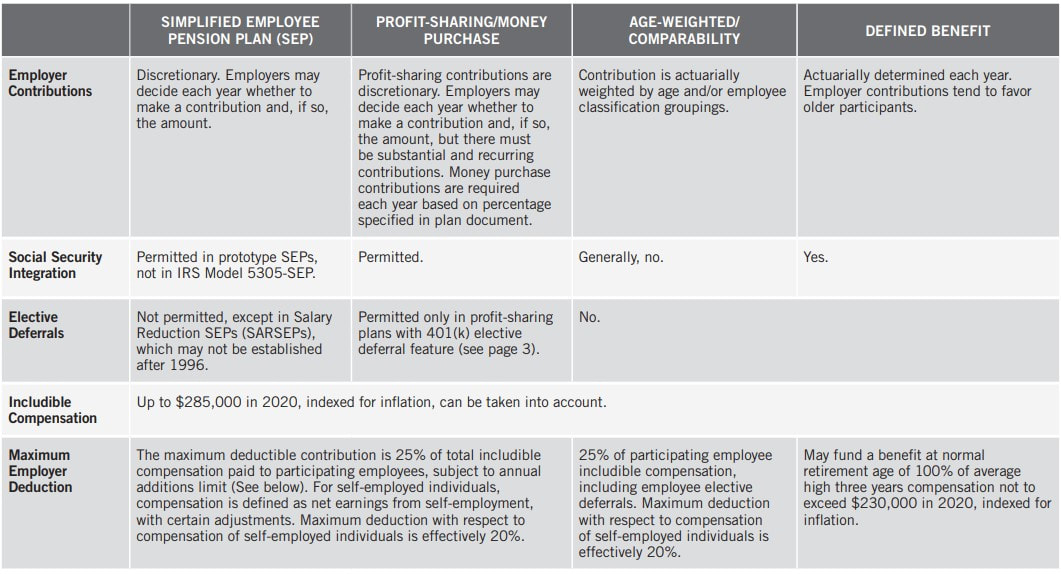

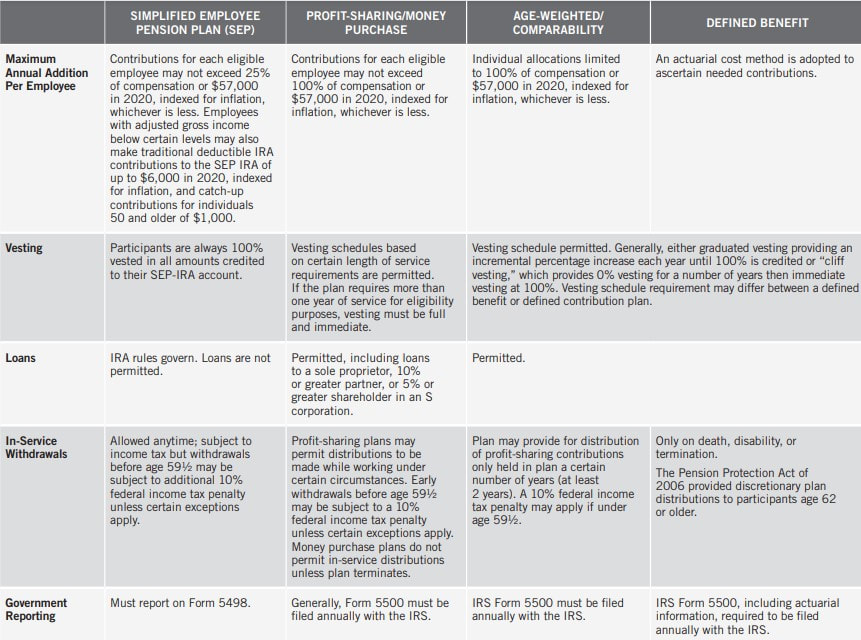

In last blogpost, we discussed employer-sponsored plans for business owners. Now we will discuss Elective Deferral Designs.

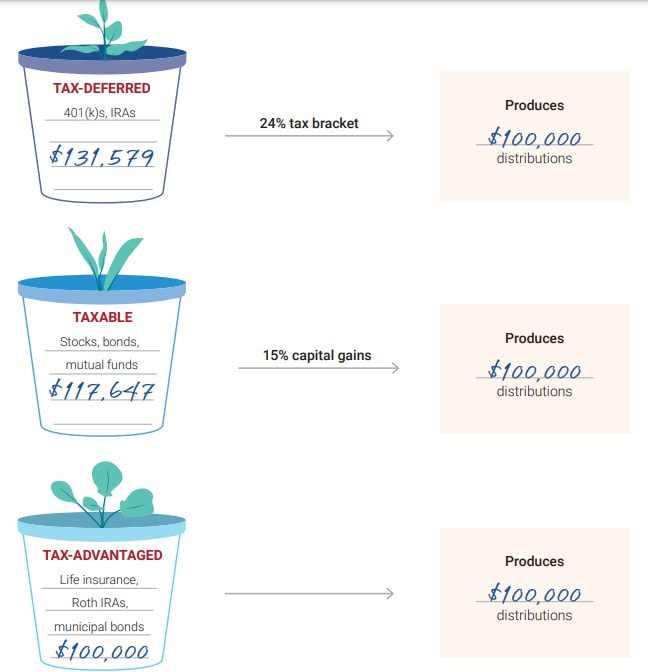

As you plant the seeds for retirement, now is the time to consider how taxes will affect you when you begin spending your savings.

The following illustration will help you understand how taxes affect your retirement plan and how to diversify assets, so you can keep more income and pay less in taxes when you begin distributions. As you understand how taxes impact the money you use to invest in the different options and how taxes impact your distributions, you will see that diversification is not only important for growth but distribution. These 5 Internal Revenue Tax Code sections put the power of life insurance to work helping you reach your financial goals: Many families use 529 plans as a way to save for future education costs due to its tax benefits, as funds in a 529 account grow tax-deferred, and that growth can subsequently be withdrawn tax-free if used for qualifying educational expenses. In addition, many states offer a tax deduction for 529 plan contributions, making these accounts even more attractive.

And while many families might not have the means to contribute more than the annual gift tax limits ($16,000 per individual, per recipient, in 2022), wealthier families have the option of ‘superfunding’ these accounts beyond this limit without using their gift tax exemption. The superfunding exception allows individuals to fund up to five years’ worth of 529 contributions to a given beneficiary in a single year, without triggering gift taxes when the contribution is made to the child’s 529 plan. For example, a parent could contribute $80,000 into a 529 for their child in 2022, and not have to use any of their gift tax exemption… as long as they do not make additional gifts to that child for five years. Given the additional years of potential compounding (with tax-free growth potential), superfunding a 529 could lead to a larger account balance by the time the student goes to college compared to making smaller annual contributions. At the same time, there are limits on how much someone might want to contribute to a 529 account. For example, because of the limited tax-free uses of funds in a 529, a parent or other contributor might not want to ‘overfund’ an account beyond what the account’s beneficiary is likely to need for college or graduate school expenses (especially if the parent has other financial priorities of their own!). On the other hand, the parent can choose to fund more and plan to change the beneficiary to a sibling or another individual who will have education expenses. And some families might even consider contributing so much into 529 accounts that it funds not only college for their children, but has enough left over to benefit further generations down the line. These ‘Dynasty 529’ plans have the potential benefit of perpetual tax-free growth, but come with several potential pitfalls to navigate (e.g., gift tax and Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax implications, as well as the possibility that a future beneficiary will use the funds for something other than education and pay the associated taxes and penalties). First introduced in the 1970s, index funds have grown in popularity over time thanks to their ability to provide broad-based diversification at (typically) very low costs, making their benefits available to investors of any level of wealth. And while mutual funds and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) have been the dominant way for investors to get index exposure, thanks to improved technological capabilities and reduced trading costs, direct indexing – buying the individual component stocks within an index – has emerged as an alternative tool with a range of potential use cases.

Historically, direct indexing was developed as a means to unlock the tax losses of individual stocks in an index – even if the index itself was up – and was primarily used only by the most affluent investors (who had the highest tax rates and benefitted the most from the available loss harvesting). However, direct indexing can be used not only to harvest tax losses but also to harvest capital gains (particularly for those taxpayers in the 10% and 12% tax brackets). In addition, direct indexing can provide tax benefits to investors who are charitably inclined by allowing them to donate the underlying shares within an index that have the largest gains, thereby helping them to maximize their tax savings. For those whose primary goal is to benefit from a more personalized indexing strategy that still gains broad market exposure while specifically adjusting for personal preferences, using a personalized index can ensure the investor’s capital will support the exact industries or companies they wish to support (while also saving on the management fees otherwise charged by more packaged ESG/SRI mutual funds and ETFs). This article from Kitches.com discusses in great details of 4 types of direct indexing -

If you had a withdrawal from your Virginia529 account(s) during 2021, a 1099-Q form was issued for tax purposes.

If a withdrawal was made payable to an account owner, a 1099-Q will be mailed to the account owner and is available online at Virginia529.com. Simply log in to your account, locate the “View My Account” tab, and select “Tax Information (1099-Q Form)” from the dropdown menu. If a withdrawal was made directly to the student beneficiary, to a K-12 school or eligible educational institution, the student will receive the Form 1099-Q in the mail. Students can log in to their Virginia529 account to review a digital copy or create a login ID if they do not already have account access. It's important to note that the account owner will not be able to view this document. Reporting 1099-Q Amounts on Your Tax Return Virginia529 is required to report withdrawals to the IRS with Form 1099-Q. Qualified education expenses include tuition, fees, books, computers and related technology, and some room and board costs for students attending an eligible college or university. Families can also take a tax-free withdrawal to pay for tuition expenses at private, public and religious elementary and high schools. This amount is limited to $10,000 per year, per student. The SECURE Act of 2019 expanded the definition of qualified 529 plan expenses to include costs of apprenticeship programs and qualified student loan repayments. Qualified distributions for student loan repayments have a lifetime limit of $10,000 per beneficiary and each of their siblings. 529 withdrawals spent on other purchases, such as transportation costs or health insurance coverage are generally considered non-qualified. If the withdrawal(s) taken on your account did not exceed the total amount of 2021 qualified higher education expenses incurred, you should not need to report the withdrawal(s) on your tax return. If, however, the withdrawal(s) exceeded your total qualified higher education expenses, consult a tax professional for more information as you may have income tax consequences. Reporting Contributions on Your Tax Return If you’ve simply been contributing to an existing 529 account you may not have to report anything on your federal income tax return. Contributions to a 529 plan are not deductible and therefore do not have to be reported on federal income tax returns. What’s more, the investment earnings in your account are not reportable until the year they are withdrawn. As for state income tax filings, Virginia529 account owners who are Virginia taxpayers may deduct contributions up to $4,000 per account per year with an unlimited carryforward to future tax years, subject to certain restrictions. Those account owners who are Virginia taxpayers age 70 and above may deduct the entire amount contributed to their Virginia529 account in one year. In addition, contributions to Virginia529 accounts are treated as a completed gift by the account owner to the student beneficiary. This means contributions up to $16,000 a year, or up to $32,000 if married, may be gift tax free. You should consult your tax advisor regarding the specific tax consequences of contributions. If you’re expecting a tax refund check this year, consider transforming it into a contribution toward your Vigrinia529 account. Tax season is upon us, but before you file, take the time to help make sure you’re not paying more than you owe. If you’re among the Americans who typically only take the standard IRS deductions instead of itemizing on your 1040, you may be missing out on some money-saving tax deductions or credits that you’re eligible for. Keep these three factors in mind that may help you save.

Charitable contributions You already know that you can deduct donations of money or goods, but most taxpayers often don't deduct enough. That's because many of us fail to keep detailed records tracking our donations throughout the year. Whether you dropped off a bag of clothing at a local charity or donated $5 at the register of your grocery store, you should be tracking all of these contributions to ensure that you get the highest tax benefit. If you didn't track this last year, sit down now and do your best to account for as much as possible. And don't forget, you may be able to include transportation costs in service to a charitable organization (like dropping off those donations or getting to and from a charity event or volunteer day). Then pay closer attention to donations this year. Reinvested dividends Reinvested dividends in a taxable investment account are treated as current income, the same as though you received them in cash. Qualified dividends, which are those held for a specific time, are taxed at a lower capital-gains tax rate (visit irs.gov to find out what qualifies as a dividend). This isn't exactly a deduction, but you may be able to cut down on your tax bill through good record keeping. When reinvesting dividends, add this amount to your basis in the security. By tracking the basis, you can reduce your capital-gains tax if you sell the security at a higher price. Earned income tax credit The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), designed to supplement wages for low-to-moderate income workers, may or may not be on your radar. Although tens of millions of people previously classified as “middle class” — including traditional white-collar workers — now fall into the “low income” bracket because they lost a job, took a pay cut, or worked fewer hours during the year. Given the interruptions and changes in employment affecting millions of workers from the widespread efforts to help control the pandemic, it may be worth talking to your tax advisor to see if you’re eligible this year. Tax-advantaged product solutions can help clients save more for retirement and potentially grow their savings faster. Most clients may be familiar with 401(k)s and IRAs, but there's another tax-advantaged vehicle to consider for retirement planning: fixed indexed annuities (FIAs).

FIAs are insurance products that offer growth potential and guaranteed income for retirement. Funds in an FIA earn interest credits based in part on the upward movement, if any, of a reference stock market index, such as the S&P 500®. Since money in an FIA is not directly exposed to stock market risk, FIAs also provide protection from loss due to market downturns. What's more, this combination of growth potential and protection comes with tax advantages that can complement other savings and investment vehicles in your clients' retirement portfolios. Here is a look at three key tax benefits of FIAs and how they can contribute to a tax-smart approach to retirement planning.

The big picture With their tax benefits and ability to provide growth potential and protection, FIAs can play an important role managing taxes within a retirement savings plan. They may complement other sources of growth potential and retirement income, including stocks, bonds and mutual funds held in taxable brokerage accounts; savings in tax-deferred accounts like 401(k)s; and other tax-advantaged vehicles such as Roth IRAs. Using a mix of these tools can be vital to helping clients minimize the effect of taxes, manage risk and provide growth potential before and after retirement. Here is an updated version of 2022 tab tables from Athene. Taxes are constantly changing. And, this could lead to unanticipated tax risk for your clients and their heirs. That’s why many individuals are not waiting until retirement to prepare. Here’s an example of what someone could do now to protect their assets and their loved ones who will inherit them.

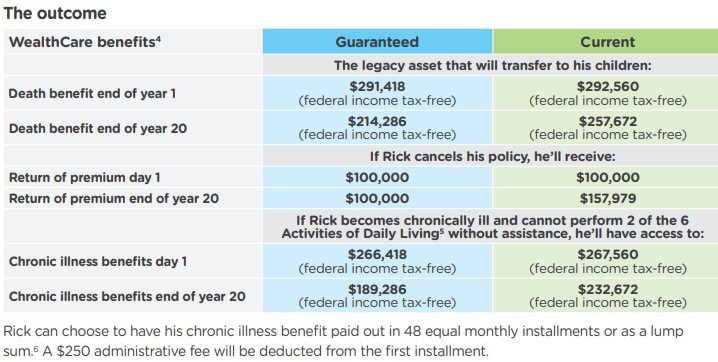

Case Study: An asset for tax diversification Rick is age 55. He and his wife, Tina have two adult children. This couple recently sold their home and moved to a condo in town. They made a nice profit on the sale, and Rick is ready to use part of the money in a tax-efficient way. Rick’s goals • Finding an asset that offers tax-advantaged growth • Creating a legacy for his children without creating tax risk for them • Establishing his plan for care Rick’s concerns • Facing market risk and losing the profit he made on his home sale • Not knowing what income and capital gains taxes will be in the future The solution In conjunction with recommendation from Rick’s tax and estate planning team, Rick purchase a $100,000 Indexed Single Premium Universal Life Insurance policy as a differentiated asset within his portfolio. This will provide the liquidity of a full return of principal, tax advantaged growth, guarantees, an income tax-free legacy for his children, and income tax-free chronic illness benefits if he would ever need care. At the time of purchase, Rick chooses the Global Multi-Index Bonus HIGH PAR Strategy which can help his death benefit grow tax-deferred over time. He’ll have principal protection and will never face losses due to market performance. The outcome Financial-planning.com has an article analyzes if Roth IRA conversion is still a risk worth taking this year, see below -

Go all out on contributions to retirement plans Didn’t max out your contribution limits last year? The IRS allows contributions for 2021 to be made through April 15, 2022. That’s three days before this year’s April 18 filing deadline, which was extended due to the Emancipation Day holiday in Washington, D.C. Some contributions are deductible, so they’ll lower the total amount of income on which taxes fall, a savings to the taxpayer. For 2021 returns being filed now, Americans could contribute a maximum $6,000, plus an extra $1,000 if aged 50 or older, to a traditional individual retirement plan (IRA) or Roth IRA. So an older married couple can put in a maximum $14,000. Traditional IRAs are generally funded with money on which taxes haven’t yet been paid, while Roth plans are fueled by after-tax dollars. Pretax contributions grow tax-deferred, with the owner paying ordinary rates on future withdrawals. While investors can also contribute money on which they’ve already paid taxes, they pay ordinary tax on withdrawals, making after-tax contributions to a traditional IRA a double tax hit. In contrast, Roth plans grow tax-free, with no levies on withdrawals. Deductions get complicated, depending on how much a taxpayer makes and whether she or a spouse has a workplace retirement plan. A traditional IRA owner who doesn’t have a workplace retirement plan (or whose spouse lacks one) or whose income is below $76,000 gets a whole or partial deduction. If a married couple filing jointly has one spouse with an employer-sponsored retirement plan, typically a 401(k), then an IRA contribution by the other spouse is no longer deductible once their joint income hits $214,000. Straightforward Roth IRA plans are a little different. The contribution limits are the same. But while there are no income limits on who can contribute to a traditional IRA, contributions to Roth plans now are limited to people who made under $140,000 last year (under $208,000 for couples). Because their assets grow tax-free and don’t bear future taxes, Roth contributions aren’t deductible. The Roth conundrum It’s still not clear what might happen to so-called backdoor Roth conversions, a mainstay of large retirement accounts and estate planning for the wealthy, under stalled legislation in Congress. While emerging versions of the Build Back Better tax-and-spending bill aim to limit or ban the ability of high earners to own Roths through indirect methods, the legislation is mired in infighting by Democrats. But some tax and retirement experts think that it’s probably safe to take advantage of their current tax benefits, even as legislators work to curb them. January 31, 2022 8:36 PMBackdoor conversions involve an investor converting a traditional IRA into a Roth. They’re a way for wealthy people to sidestep the income limits for direct contributions to a Roth. An early version of the House bill banned conversions of after-tax dollars in IRAs and 401(k)s. The House passed a somewhat softened version of that proposal last November. The legislation, which has to be passed by the Senate, would outlaw so-called mega-backdoor Roth conversions starting Jan. 1, 2022. The strategy came under a spotlight when ProPublica showed how PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel used it to transmute less than $2,000 worth of pre-IPO shares into a $5 billion account. The bill would still allow regular Roth conversions but would ban people with higher incomes from doing them starting in 2032. Last December, the Senate offered its own version of Build Back Better that proposes those same limitations. The backdoor strategy involves using hefty after-tax contributions to a 401(k) plan that permits them. Under IRS rules, a taxpayer could put as much as $58,000 last year into a workplace retirement plan ($64,500 for those 50 or older). One chunk of the money reflects the maximum pre-tax amount of $19,500 ($26,000 if 50 or older), while the remainder, up to $38,500, reflects after-tax dollars. The limits include any company matches. The taxpayer then converts her 401(k) to a tax-free Roth. The higher amounts can swell a retirement portfolio far beyond what direct contributions to an ordinary Roth can. Christine Benz, Morningstar’s director of personal finance, wrote in a Jan. 21 research note that it’s “unlikely” that when a final bill makes it to President Joe Biden’s desk for signature, if indeed one does, the proposed curbs would be retroactive to the start of this year. “Given that these contributions and conversions are currently allowable,” she wrote, financial advisors have “been urging their clients to go ahead with them until the law officially changes." Benz quoted Aron Szapiro, the head of retirement studies and public policy for Morningstar, as saying that the likelihood of a retroactive ban on after-tax contributions is "close to zero.” Of course, nothing’s final on Capitol Hill until it’s final. Nonetheless, Benz wrote, “given that backdoor Roths are one of the few mechanisms that higher-income heavy savers can use to achieve tax-free withdrawals and avoid RMDs in retirement, many such savers are apt to conclude that it’s a risk worth taking." There may be a silver lining for crypto investors selling at huge losses during the recent market turmoil: a quirk in the Tax Code that lets people minimize what they’ll owe the government down the road.

Unlike stocks and bonds, cryptocurrencies aren’t subject to federal rules that bar people from claiming deductions if they sell an asset at a loss and then buy an identical or similar asset within 30 days before or after the sale. That provides a unique opportunity for people suffering steep losses to sell and reap future tax savings, then buy more virtual tokens at cheaper prices, according to crypto tax filing software firms. This is a great time to store your capital losses, because when you exit the market at a future date at a huge gain, you can use these losses After surging 60% in 2021 — and touching an all time high of nearly $69,000 in November — Bitcoin has fallen 20% to under $37,000 this year. The impact of crypto’s January turmoil won’t show up on investor’s 2021 tax returns. However, thousands of crypto investors who piled into the asset class last year must account for those investments as they file their returns during the next few months. Investors who sold crypto at a loss and then purchased similar assets at a lower price — a move that some refer to as wash sales — are free to take advantage of the tax strategy, according to TaxBit, a crypto tax software company. Some Democrats tried to close the loophole in a roughly $2 trillion spending bill that failed late last year. “Tax-loss harvesting” Strategy Under the strategy, investors can use their losses to offset any gains in a given year. If they don’t have gain to offset, they can deduct up to $3,000 in losses from ordinary income. Any excess capital losses above that amount can be used to lower tax bills in subsequent years. With all the tax legislation oxygen taken up by BBB, many have forgotten about Secure 2.0, but it’s still waiting to see the light of day.

Keep an eye on this bill. Of all the the bills that could be enacted in 2022, this one has the best chance, having passed out of committee unanimously, with full bipartisan support. See if you may be affected by these proposals in 2022: ‘Rothification’ Secure 2.0 includes provisions allowing both SIMPLE and SEP Roth IRAs. In addition, plan catch-up contributions would be required to be made to Roth plan accounts, and plans could allow participants to have employer matching contributions made as Roth contributions. Other Proposed Changes

Mutual funds generate capital gains taxes each time they sell an underlying holding that has appreciated, even if an individual investor holds on to her fund. So that cost is passed on to her. By contrast, ETFs use an obscure tax loophole to cash in on appreciated holdings by swapping assets with a buyer — in this case, major banks.

For example, a fund sells an appreciated stock in its “basket” of shares to a bank and immediately buys back “substantially similar” shares. Because no cash has traded hands, there’s no capital gains tax on those profits. Or an ETF can sell a losing stock, deduct the loss, then buy back similar stock. The deduction boosts the returns of the fund. Of course, when an investor sells her ETF, she owes capital gains tax on the profits. But until she does, the capital gains taxes on internal trades made to keep the fund in line with its benchmark are “washed away.” With active trading strategies, the tax perk for the new semi-transparent and opaque ETFs is even more significant. As well as potentially more prone to scrutiny. Sen. Ron Wyden, who heads the Senate Finance Committee, called in Sept. 2020 for an end to ETFs’ use of “in-kind” transactions to avoid triggering capital-gains taxes. In 2001, Vanguard, the world’s second-largest asset manager, acquired a patent for a novel, tax-efficient fund structure that blends a mutual fund and an ETF by bolting on an ETF share class to its existing stock mutual funds. The patent expires in May 2023, which could open the flood gates to lookalike funds from competitors — and to greater scrutiny by regulators and critics, who argue that the structure’s tax benefits are controversial.

Vanguard’s secret sauce has several benefits. Ordinarily, investors in a mutual fund owe capital gains taxes when that fund sells stock. The Vanguard patent uses an obscure, decades-old tax loophole to eliminate those levies both in a mutual fund and an ETF. The loophole says that when withdrawals from a fund are paid with stock, not with cash, there’s no capital gains hit for the investor. For withdrawals, Vanguard uses rapid trades to whisk appreciated stock out of both a mutual fund and its sister ETF, then rapidly injects stock back in. A 2019 Bloomberg investigation detailed how those so-called “heartbeat” trades are fueled by big banks. Investors can swap their mutual fund shares for shares in a “sister” ETF, all without owing taxes on the profits. The tax erasure not only reduces taxes on paper profits but also allows investors to defer paying taxes on their profits until they ultimately sell their mutual fund. Because the patented structure involves two classes of shares, it gives investors the choice of holding a single investing strategy as a mutual fund or as an ETF. Vanguard’s secret method bolts an ETF onto an existing mutual fund, in contrast to competitors that issue stand-alone ETFs. While the entire investment holds the same securities, the ETF portion has a separate class of shares. The structure allows Vanguard “to have an ETF product that is almost identical to its mutual fund counterpart, which gives investors a wider range of product choice,” Shapiro said. “One fund, two share classes — that is unique.” Prior Cerulli research cited in the firm’s U.S. Exchange-Traded Fund Markets 2021 report showed that nearly four in 10, or 38%, of ETF issuers were considering adopting the Vanguard model once its patent expires. “Managers considering launching active ETFs should also keep an eye on the dual-share-class structure used by Vanguard, which comes off patent in 2023,” the Cerulli ETF report said. The benefit to financial advisors is that they “wouldn’t have to dig into specific differences between what’s in the mutual fund and what’s in the ETF,” Shapiro said. Still, he added that “it’s an open question” whether the new breed of active ETFs will get a green light to use the Vanguard recipe, given the controversy over its tax benefits. “It’s not clear that the SEC would approve it,” he said. If you haven’t done so already, it’s time to get ready to file your taxes. Whether you use a tax professional or prepare your taxes yourself, the first step is to get organized, and a tax preparation checklist can help you do that. Here are some tips to help you get started.

*Collect your income records : Employers/companies send out W-2s and 1099s by the end of January. Review these documents carefully as soon as you receive them; if you find a discrepancy, you have plenty of time to get a corrected document. *Collect copies of year-end bank, brokerage, and investment account statements: These may contain needed cost-basis, transaction type, gain/loss information. They can also serve as proof of IRA contributions. *Organize and validate your deductible expenses and eligible tax credits (some may include) : *Work-related receipts *Receipts/payment records for charitable donations *Payment records of eligible medical co-payments *Education costs/student loan interest *Mortgage interest statement *Homebuyer tax credit *Check out one-time benefits that might apply: Investments in certain energy-efficient products (such as water heaters, central air conditioners, new windows and doors, and insulation) could make you eligible for tax credits this year. If you installed a solar energy system (or other type of renewable energy system) you may be eligible for a tax credit. Details about these types of tax credits are available at: www.energysavers.gov. **Locate last year’s tax return: You may need to reference important information for this year’s return. |

AuthorPFwise's goal is to help ordinary people make wise personal finance decisions. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed