A. The premium assistance tax credit is intended to make health insurance purchased on an exchange more affordable for the "lower income" - which is actually broadly defined to include everyone up to 400% of the Federal Poverty Level. As income rises, the premium assistance tax credit is slowly phased out, until eventually it provides no benefit at all.

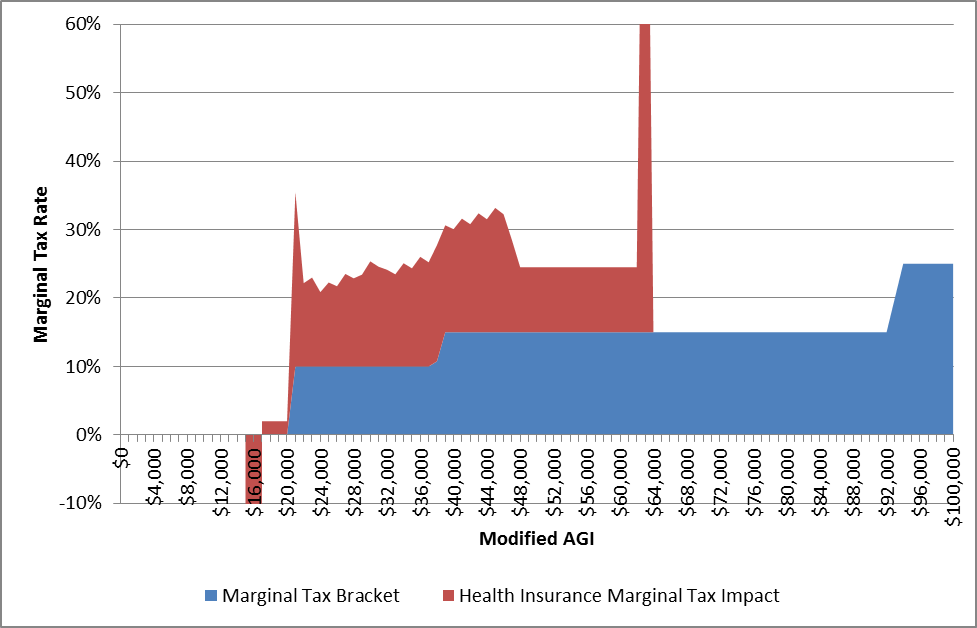

However, the reality is that because the premium assistance tax credit phases out as income rises, it indirectly serves as a surtax that triggers higher marginal tax rates for those who are phasing the credit out. And the marginal impact is actually quite significant; at relatively modest levels of gross income from $25,000 to $50,000 of income, the premium assistance tax credit effectively doubles the marginal tax rate (to more than 30%) for those who are purchasing health insurance from the individual exchange.

The end result doesn't mean that it's a good idea to avoid generating income - as long as the marginal tax rate is less than 100%, it is still a gain for you. Nonetheless, the introduction of the premium assistance tax credit may mean a whole new level of in-depth year-to-year tax planning for those with relatively modest incomes, who can be subject to surprisingly high marginal tax rates under the new rules.

The Federal Poverty Level thresholds are adjusted for inflation each year, and are determined based on the number of people in the household. For example, in 2013, the FPL was $11,490 for an individual and $23,550 for a family of four, which means at least some premium assistance credit is available for households with incomes up to $45,960 for individuals and $94,200 for a family of four.

“Income” for the purposes of the premium assistance tax credit and the FPL is based on modified Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), which means AGI increased by any income not reported due to the foreign earned income or housing cost assistance exclusions, any tax-exempt interest (i.e., municipal bond income), and any Social Security benefits that were excluded from income. In other words, household income for the purposes of the credit will include all bond interest (taxable or tax-exempt), and all Social Security benefits (taxable or tax-exempt).

For example:

Bill is a single 35-year-old non-smoker who earns $25,000 per year. His income is 218% of the $11,490 FPL (in 2013) for a household size of 1. Accordingly, this puts him roughly midway between the 6.3% and 8.05% threshold for maximum premium; his exact threshold is 18/50ths of the way from 200% to 250% of the FPL, so his maximum premium is 18/50th of the way between 6.3% and 8.05%, which means his maximum premium is 6.93% of his $25,000 income, or $1,733/year. If the actual premium for the second lowest cost Silver plan in his state is $300/month (or $3,600 per year), Bill’s premium assistance tax credit will be $1,867 (which brings his premium down to the maximum cap of $1,733/year). Accordingly, Bill will pay $144.42/month for his health insurance, with the remaining $155.58/month covered by the premium assistance tax credit. Notably, if Bill chooses to buy a different plan besides the Silver, which may cost more or less, his premium assistance tax credit will continue to be $155.58/month, but his share of the premium will be the remainder left over (whatever that comes out to be).

How The PATC Can Boost The Marginal Tax Rate?

The complication that arises with the PATC is that, because it is calculated based on income (or at least, the maximum premiums owed are calculated based on income, which indirectly means the credit is determined by income), generating more income not only creates the usual tax burden associated with income, but it can also trigger a phaseout of the PATC (at least up to 400% of the FPL, as beyond that point there is no PATC at all).

For example:

Ted and Janet are a 45-year-old couple with two children, and their combined income is $50,000/year. With a $12,200 standard deduction and four $3,900 personal exemptions, their taxable income would be $22,200, putting them near the lower end of the 15% tax bracket. In addition, their income for a family of four would put them at 212% of the FPL, capping their health insurance premium at 6.72% of income, or $3,360; if the cost of a Silver plan for the family was actually $1,000/month ($12,000 per year), their premium assistance tax credit would amount to $8,640/year or $720/month, bringing their own out-of-pocket premium down to only $280/month for the family.

If the couple earned another $10,000 (rising from $50,000 to $60,000 for the year), their income would rise to 255% of the FPL, which would increase their maximum premium threshold to 8.19% x $60,000 = $4,913/year. As a result, they would be required to pay another $1,553 of health insurance premiums for the family, in addition to owing another $1,500 of taxes (at a 15% tax bracket on $10,000 of income), to a total burden of $3,053 for an extra $10,000 of income. Thus, the net effect of the changing income-related threshold for the premium assistance tax credit it to boost the couple’s marginal tax rate from 15% to a whopping 30.53%!

Marginal Tax Rate Increases At Varying Income Levels

Ultimately, the impact of the PATC on someone's marginal tax rate will depend on where exactly they fall on the income spectrum (and based on their family size as well, as the FPL thresholds vary depending on the number of family members in the household). The figure below shows how the marginal tax rate of a middle-aged married couple changes as their income rises, assuming they claim a standard deduction ($12,200 in 2013), two personal exemptions ($3,900 each in 2013), and have an annual health insurance premium of $7,000 for the two of them ($583/month before premium assistance tax credits).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed